Can Social Media Ever Be Truly Democratic

- Jan 16

- 4 min read

BY: FAITH OBUM-UCHENDU

Editor: ESHAL UZAIR

Whether social media can ever be truly democratic depends less on technology itself than on how societies choose to govern participation within it. At its best, social media promises open access and the ability to participate in public discourse regardless of geography or status. At its worst, it becomes a space shaped by exclusion, surveillance, and unequal power. Recent government interventions, including Australia’s proposal to restrict social media access for children under sixteen, illustrate a broader global pattern: when faced with digital risk, states increasingly prioritise control over inclusion. This trend suggests that social media cannot be fully democratic while participation is treated as a privilege to be restricted rather than a right to be supported.

A core principle of democracy is equal access to the public sphere. Historically, this has meant access to newspapers, public meetings, protest, and political debate. In the twenty-first century, social media has become one of the primary spaces where these democratic activities occur. Young people use platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, and X not only for entertainment but also to encounter political ideas, mobilise around issues such as climate change and their causes, and engage with social justice movements. The global school strikes inspired by Greta Thunberg, for example, relied heavily on social media to organise across borders. Restricting access to these platforms therefore has democratic consequences, because it limits who is able to observe, engage with, and contribute to political life.

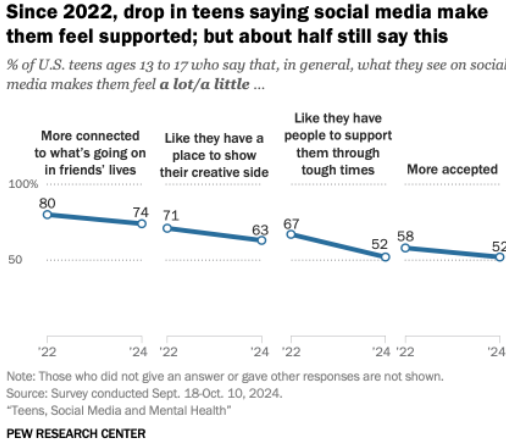

Supporters of age-based bans argue that democracy must be balanced against protection, particularly given rising concerns about youth mental health. Evidence from multiple countries supports the claim that adolescent mental health has worsened in recent decades. In the UK, NHS data show a sharp rise in anxiety and depression among young people, while studies in the United States link heavy social media use to increased rates of loneliness and sleep disruption. These concerns cannot be dismissed. However, democratic governance requires proportional responses. Correlation does not prove causation, and many researchers, including those at the Oxford Internet Institute, have found that the relationship between social media use and mental health is small, complex, and highly dependent on context, as social media does not affect all users in the same way. For many marginalised young people, digital spaces provide support that is unavailable offline. Research by UNICEF and the Pew Research Center shows that LGBTQ+ youth, disabled young people, and those living in rural areas are more likely to rely on online communities for social connection and identity formation. Removing access to these spaces does not simply eliminate harm; it can also remove vital sources of belonging. A democratic public sphere cannot be considered equal if it protects some by silencing others.

The question of democracy also extends to freedom of expression. Even in countries without explicit constitutional free speech protections for minors, democratic systems rely on the gradual development of civic voice. Political awareness does not begin at eighteen; it is shaped over time through exposure, discussion, and participation. When governments exclude young people from digital spaces where political discourse increasingly occurs, they risk creating a form of delayed citizenship. This undermines democracy by treating political engagement as something that begins suddenly at adulthood, rather than as a skill developed through experience.

Enforcement mechanisms further weaken the democratic potential of social media. Age verification systems, whether biometric or identity-based, raise serious privacy concerns. The European Union’s debates over digital ID and the UK’s Online Safety Act have highlighted the risks of normalising surveillance in everyday communication. Democracy depends not only on access but also on autonomy and privacy. When participation requires constant verification, citizens are less free, not more protected. Introducing such systems for young people in particular risks teaching them that surveillance is a normal condition of public life.

Beyond age restrictions, the structure of social media platforms themselves presents additional challenges to democracy. Algorithms prioritise engagement over accuracy, amplifying sensational or polarising content. Disinformation campaigns, such as those seen during the 2016 US election and the COVID-19 pandemic, demonstrate how easily democratic debate can be distorted. However, these failures point to the need for reform rather than exclusion. Holding platforms accountable for transparency, algorithmic design, and content moderation addresses democratic weaknesses without undermining participation itself.

The Australian proposal is therefore best understood as part of a wider international response driven by social anxiety about technological change. While such policies may reassure the public, they risk setting a precedent in which democracy is preserved by narrowing access rather than strengthening responsibility. A truly democratic approach to social media would involve digital education, platform regulation, and youth inclusion in policymaking. It would recognise young people not only as vulnerable users, but as emerging citizens.

In conclusion, social media can only be truly democratic if societies resist the instinct to govern it through exclusion. Democracy is inherently messy, risky, and imperfect, but it depends on participation rather than protection alone. When governments respond to digital harm by restricting access to the public sphere, they weaken the very democratic values they claim to defend. The challenge is not to decide who should be kept out of social media, but how participation can be made fairer, safer, and more accountable for everyone.

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Australia’s Youth: Mental Health and Wellbeing, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/mental-illness

Oxford Internet Institute. (2020). The Relationship Between Social Media Use and Well-Being, https://www.oii.ox.ac.uk/news-events/internet-use-statistically-associated-with-higher-wellbeing-finds-new-global-oxford-study/

Pew Research Center. (2022). Teens, Social Media and Mental Health, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2025/04/22/teens-social-media-and-mental-health/

UNICEF. (2021). The State of the World’s Children: On My Mind, https://www.unicef.org/media/114636/file/SOWC-2021-full-report-English.pdf

boyd, d. (2014). It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens. Yale University Press, https://www.danah.org/books/ItsComplicated.pdf

Twenge, J. M. (2019). iGen. Atria Books.

Comments